Capitalism is calling North Korea

A North Korean flag flutters at the propaganda village of Gijungdong. (Photo: Reuters/Kim Hong-ji)

A well-known fact about me (because I never shut up about it) is that I was a Sociology major. And while the trauma of a high-pressure academic environment has caused me to repress most of my memories from my time in university, I’ll never forget the ideological debate that was brought up in almost every class I took: capitalism vs communism.

As history has shown us, communist states are never actually fully communist. While their governments are authoritarian, market activities and private property still exist in these states. Just look at how China, Cuba, Vietnam, Laos, and even North Korea, is marketizing at a faster rate than they have in the past seven decades. And the cause of this sudden and rapid change? Surprisingly, it’s because of the mobile phone.

Phone fever sweeps North Korea

I’ll be honest, I don’t know much about North Korea. But I guess that’s the point, right? They’re reclusive by choice, which is quite an effective part of their nationalist and anti-capitalist propaganda that has kept them isolated from the rest of the world since 1945. This isolation has also set them back in terms of communication and technology.

But as it turns out, they aren’t as disconnected as we think. In fact, last week, North Korea was hit with a massive internet outage, with government portals taking the brunt of the suspected attack. The outage was so effective that the internet in the entire country was taken offline.

It’s worth noting that only about 1% of the country’s population of almost 26 million has access to the global internet—but, surprisingly, millions are connected to an internal network.

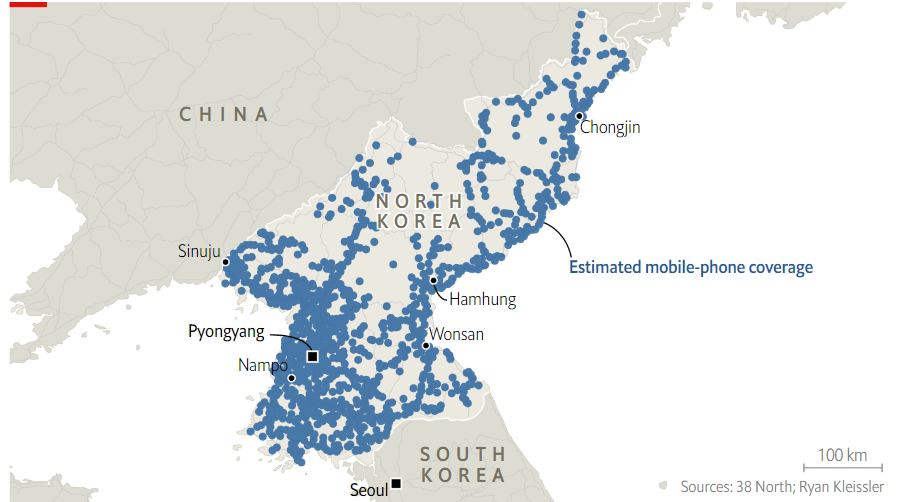

Over a thousand cell towers were detected in North Korea. (Source: The Economist)

A recent study by Martyn Williams and Natalia Slavney of the Stimson’s Center’s 38 North program found over 1,000 cell towers in the country. These towers weren’t just in city centers, either. Some of them were deep in the countryside, and researchers note that there are likely more towers that their satellites couldn’t detect.

To learn more about how mobile devices are used in the country, researchers interviewed 40 defectors. From these interviews, and from previous data, researchers were able to estimate that there are around 6.5 to 7 million subscriber lines—though they also note that there are likely more lines than there are users, as the North Korean government limits contracts to one per person, and each contract comes with a limited number of cheap minutes. Defectors shared that line subscribers often persuade their friends and family who don’t own phones to sign up for subscriptions on their behalf.

The devices are usually mid-level Chinese Android phones, which the government rebrands and configures to limit their functions. From what researchers can tell, the networks are also quite old. They were first set up in 2008, and are still running on 3G technology—meanwhile, across the border, South Korea is already working towards 6G.

The marketplace is now mobile

So if they’re not connected to the global network, and the state limits their functions, what exactly are these phones used for? Apparently, capitalism.

More than 90% of the respondents to Williams and Slavney’s study said that the mobile phones were used daily, with many of the calls made to family members and traders. Poor infrastructure in North Korea means that there aren’t many landlines, so mobile devices fill in that gap, and are vital for participating in the private marketplace—which is now becoming a key source of income for many North Korean citizens.

Over the past ten years, private activity has grown from about 28% to now making up 38% of the North Korean economy, overtaking state-led agents as the country’s biggest economic actor. Meanwhile, government-initiated programs went down from 37% to 29%.

The number of private merchants has also skyrocketed by more than 400% from 338 in 2011 to 1,368 in 2018, before sharply dropping due to economic difficulties, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. But allowing private marketplace activities has opened new sources of income for North Koreans, and improved their GDP by 3.9% in 2016—the fastest growth the country had seen in 17 years.

While the current numbers are murky, since the NK government does not answer questions from foreign reporters and rarely speaks publicly about their economic conditions, things seem to be changing within those tightly-closed borders. Kim Jong Il, father of Kim Jong Un, must be rolling in his grave, seeing his people participating in the economic activities that he abhorred—and his son openly allowing it.

The truth is that communism only works if everyone, at a global scale, participates. In the case of North Korea, their isolation and refusal to participate in the global economy pushed them into a corner, and led them to struggle when hard times hit.

It was almost inevitable that at the height of economic strife, Kim Jong Un decided to loosen the reins and forego the strict, anti-capitalist policies of his father. I wouldn’t be surprised if he eventually decides to abandon them completely, since he’s already pushed for the expansion of the consumer economy and opened the country to tourism since his reign began in 2011.

As North Korea shreds the borders it once set around itself, mobile devices and connectivity will become a central part of their development—and capitalist activities will keep their people from starving, amidst economic downturns, droughts and famines.

So it looks like capitalism wins again.